Indianapolis Motor Speedway celebrates 100th anniversary of the Indy 500.

by Rick A. Richards

If there is any doubt about the impact the Indianapolis Motor Speedway has had on Indiana, look no further than the state's commemorative quarter. While other states featured the face of a famous person or their state bird, or some other landmark, the obverse of Indiana's quarter is a racecar.

This year, as IMS celebrates the 100th anniversary of its first 500-mile race, the role the speedway has played in Indiana's history and the economic impact it has had are front and center.

The idea for an automobile test track first surfaced in 1906 when entrepreneur Carl Fisher of Greensburg proposed it. Two years later, Fisher and associate Lem Trotter obtained an option to buy four adjoining 80-acre tracts of farmland northwest of Indianapolis. Years later, Fisher would make his mark by developing Miami Beach in Florida.

In 1909, a 2.5-mile track opened and in August, two motorcycle races were held on the crushed rock and tar racetrack. The surface wasn't appropriate for racing and that led to the track being covered in street paving bricks. In 1910, a 200-mile automobile race was held and in 1911, the first 500-mile race was held.

Doug Boles, an attorney, former partner in Panther Racing and director of public relations for IMS, says the milestone anniversary has been a time for officials at the speedway to take a look at its role in the state today.

“We're trying to get back to our roots and the traditions of the speedway,” says Boles. “This place is all about tradition and families. From our standpoint, we have to look at the event and determine what the things are that are important for us to maintain, and what can we do to attract a younger crowd.”

Like any traditional event, Boles says, it's vital to maintain the things that excite people and encourage them to come back year after year, but an event can't become stagnant to the point where it is too predictable.

“We have thousands of fans who have been coming to the track for 40 years or more. We want to know what excites them,” says Boles. “But we also want to remain fresh so we can connect with younger fans.”

And Boles isn't just talking about benefits to speedway ownership, but the impact it has on Indiana as a whole. According to a study complied by the National Motorsports Coalition in 2010, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Indianapolis 500 are the third-most-beneficial auto racing locations and events in the United States.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the Indianapolis 500 contribute more than $727 million to Indiana's economy, and Boles says IMS wants to increase that. The impact of the Indianapolis 500 alone is $336 million – more than four times the $104 million economic of the Indianapolis Colts, according to statistics from Purdue University.

The only racing areas contributing more to their states are the area around Charlotte, N.C., which contributes more than $6 billion to the North Carolina economy, and the Daytona International Speedway, which contributes $2.1 million to Florida.

Boles says IMS is reaching out to younger fans this year by allowing them and their parents to buy a pass to the garage and see drivers and their cars up-close. “The biggest thing we can do to ensure the future of the event is to reach out to new fans and we think this is a way to do that.”

He admits it is difficult to lure fans in the current economy, but as long as fans feel they are getting value for their ticket price the job is easier. “While we've been around for 100 years, for a long time we didn't have any competition from the Colts or Pacers, or for fans in Northwest Indiana, from the Bears or Bulls.”

As IMS celebrates a century of racing by inviting all living drivers to this year's race and putting 67 of the winning cars on display in the Hall of Fame Museum at IMS, Boles says the impact Northwest Indiana has had on the track isn't being overlooked.

While the names may not be as famous as multiple winners A.J. Foyt, Al Unser or Johnny Rutherford, the impact of those from Northwest Indiana involved in the Indianapolis 500 has been significant.

Johnny Pawlowicz (he shortened his name to Pawl) of Crown Point competed as a riding mechanic in 1936 and 1937, and continued to work as a race mechanic through the early 1960s. In the 1940s, he opened a racing business at the southeast corner of U.S. 30 and Indiana 55 near Crown Point, and one of his first customers was a “region racer” named Murrell Belanger.

Pawl was a pretty good business owner, too. In the mid 1950s, he purchased the entire midget racing operation of Kurtis-Kraft in Southern California, making him the sole supplier of custom-built midget racecars in the country.

Belanger, also of Crown Point, raced locally, but was better known as a car owner. In 1951, he financed the car and team that Lee Wallard drove to victory lane.

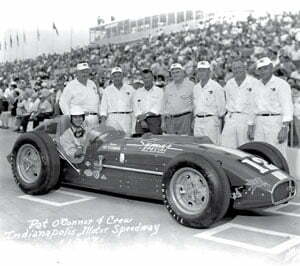

Another customer of Pawl's was Ray Nichels of Griffith, who was a chief mechanic in 12 Indianapolis 500s, including that of 1957 pole winner Pat O'Connor. He also was an Indy Car and NASCAR owner for Bobby Allison, A.J. Foyt, Roger Penske, Richard Petty, Al Unser and Bobby Unser.

He went on to found Nichels Engineering, owned two Northwest Indiana airports and was a business associate of Paul Russo of Hammond.

Together, Nichels and Russo built a homemade car known as “Basement Bessie” that finished ninth in the 1950 Indy 500. The car ran with the leaders for much of the race, which was shortened by rain at 345 miles.

Without a doubt, one of the best Indy Car drivers to come out of Northwest Indiana was Art Cross of Rolling Prairie. He drove in four Indy 500s, was named the very first rookie of the year in 1952, and one year later, he finished second.

After his four-year racing career, Cross returned to farming in LaPorte County and later ran a heavy equipment business.

It is those kinds of connections that so weave the history of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway into all corners of Indiana, says Boles.

“This is truly an asset for all of Indiana,” he says. “We don't have to do a lot of advertising because it is such a tradition, but we are active on Facebook and Twitter, and we do a lot of billboard advertising in Indianapolis.

“The reason we don't do a lot of advertising,” says Boles, “is because we still benefit greatly from ticket sales renewals. Once people come and experience the event, they want to come back.”

Boles comes by his affection for the Indianapolis Motor Speedway naturally. His father was a U.S. Auto Club Yearbook editor, and for years the family traveled to USAC events all over the Midwest. USAC is the former sanctioning body for the Indianapolis 500.

“One of the things we're looking at this year is what can we do beyond the track to excite fans,” says Boles. “We're going to go out to the state's colleges for events and encourage students to come to the track in May.”

Once those young people come, Boles says IMS is convinced they will become the fans that cement the event's fan base far into the future.